4 Mar 2020

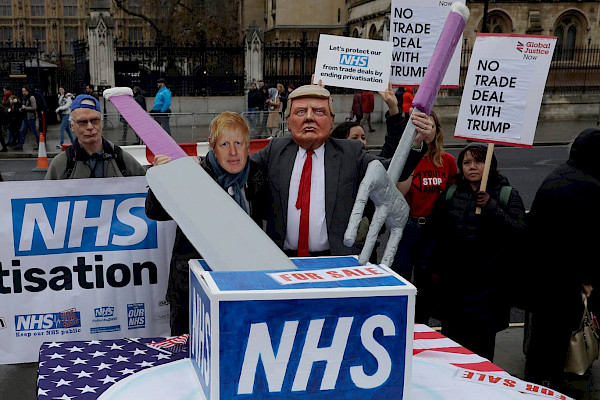

The NHS is not safe from a Trump trade deal.

- Existing and future levels of privatisation in the NHS could be locked-in

- Our ability to regulate drug prices may not be fully protected

- The NHS could be paying high prices for longer because of extended monopoly protection on new drugs

Email your MP now to ask the trade secretary to respond to these key threats

The following blog was originally published here at Global Justice Now

by Heidi Chow

The government published its long-awaited negotiating objectives for a US-UK trade deal this week which included categorical statements that the NHS and drug prices are not on the table. But this does not represent a victory for all who want to protect our NHS. These are just empty words because papers leaked from the trade talks that have taken place so far, reveal that the rules which affect the NHS and drug prices have been already been discussed. And the UK negotiating objectives show that there is still plenty that has been left on the table that poses serious risks to our NHS.

The government says: "The NHS is not, and never will be, for sale to the private sector" but this is blatantly not true as private companies including US healthcare firms already operate in the NHS. Following the Health and Social Care Act 2012, market-based approaches were significantly extended with a large number of contracts being awarded to private providers. In 2018/19 alone, the NHS spent £9.2billion on health services delivered by the private sector. This level of privatisation within the NHS and any expansion of this, could all be locked-in through a trade deal with Trump.

In spite of the government's rhetoric in its negotiating objectives, the NHS is not protected from a trade deal with the US. To see why we need to go beyond platitudes and engage in some of the details. Here are three reasons why the NHS is still on the table:

1) The government's objectives for a US-UK trade deal do not include any commitments to properly exclude the NHS

According to World Trade Organization rules, the NHS can only be excluded from trade deals if there is no other competition with other health providers. However, the NHS competes externally with private healthcare and also has private providers operating within it and so would not be exempt under these rules.

The NHS could be excluded if trade negotiators agreed to use an approach known as positive listing for services which means that only the named services would be included in a trade deal and everything else is off the table. However, the leaked trade papers showed that the US is demanding a negative listing system which works the opposite way - all services are on the table unless specifically exempted. This is a much more aggressive system as its starting point is that all services are included in the trade deal. It also relies heavily on trade negotiators being able to identify every single health service that the NHS represents to exempt it, line by line. This is a complex process, subject to mistakes and would not exclude future services that have not been developed at the time of negotiations.

A more secure way to exclude the NHS would be to apply a broad watertight carveout for public services based on the definition by the European Public Services Union which would be able to effectively exclude the NHS (and other public services) from the trade deal.

The UK negotiation objectives do not rule out negative listing, do not commit to excluding all services in the NHS and do not commit to a broad watertight carveout. Without these commitments, the NHS is effectively on the table – regardless of government rhetoric.

2) The government's objectives for a US-UK trade deal do not provide robust protection to regulate drug prices

The US pharmaceutical lobby has long-complained about not getting high enough prices for its medicines in the UK - even though the UK drugs bill has risen 22% in the last five years and the NHS is increasingly having to reject or ration drugs because of high prices. The industry wants more and has been lobbying the US government to use US-UK trade negotiations as a way to force up drug prices.

Their demands are reflected in the US negotiation objectives with demands to tackle "government regulatory reimbursement regimes". This means that the UK regulatory body NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) which assesses new drugs based on their cost-effectiveness for the NHS in England and other schemes that regulate drug prices - are all under threat.

These schemes are seen by the US as “discriminating” against high priced US drugs and therefore prevent full market access for US drugs. Attempts to weaken NICE, for example by watering down its pricing thresholds, could potentially lead to higher prices for all drugs and not just US drugs as NICE rules are applied to all new drugs.

The UK negotiating objectives make no commitments to reject all demands to weaken or undermine NICE. Without this commitment, the prices that the NHS pays for drugs is on the table.

3) The government's objectives for a US-UK trade deal do not rule out discussions on all forms of monopoly protections given to new drugs

Patents provide a minimum of 20-year monopoly for new drugs where no other company can make or sell that drug during that time. The government has committed to "secure patents…that do not lead to increased medicines prices for the NHS" but this does not seem to extend to discussions on another form of monopoly which could mean increased prices for new drugs.

Data exclusivity is where a new drug’s clinical test data cannot be used by anyone else to develop a cheaper alternative for a certain period. Without access to this clinical data, it would be very difficult for another manufacturer to produce the same drug to drive down prices – even if the drug is off-patent.

In the leaked trade papers, data exclusivity was extensively discussed. With no commitment on data exclusivity, the NHS could still be facing increased drug prices which means drug pricing is effectively still on the table.

What can be done?

None of these threats have been explicitly ruled out by the government so far which means the NHS stays on the table. Government rhetoric is not enough to protect the NHS. At this point, to protect the NHS, we need to oppose this toxic trade deal. Enshrining protections in domestic legislation would also keep it safe from these types of provisions in any trade deal and we need to call for parliamentary powers of scrutiny and democratic oversight over trade negotiations.

You can also help by taking our latest campaign action to pressure the government on these points. By taking this action, you would be helping to force the government to say whether they would take the steps needed to genuinely protect the NHS and raising awareness among MPs to not just accept government claims at face value and instead wake them up to the reality that our NHS is still under threat from a US trade deal.