4 Aug 2025

Guest blog: Jonathan Tyler, Passenger Transport Networks

This blog is adapted from a presentation given on 24 June as part of We Own It’s live event, Make Great British Railways Great

Railway timetables: the problem

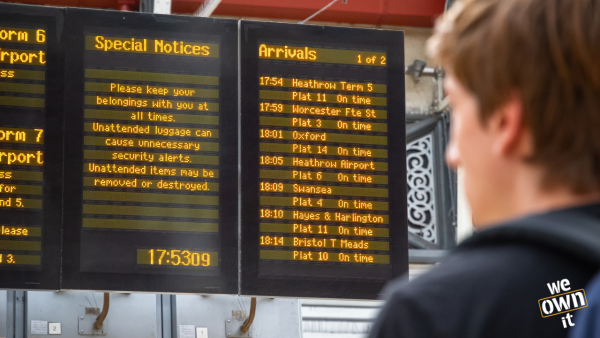

Timetable (definition): noun. A chart showing the departure and arrival times of trains, buses, or aircraft.

The current timetable for Britain’s railway contains good features, but overall it is a mess - one that the rail industry has to date shown little interest in fixing, even if that means risking loss of income should passengers choose cheaper, faster and less complex modes of transport.

- All sense of a national network has been eroded. There is virtually no promotion of the availability and benefits of the national network as each operator focuses its marketing, maps and publicity on its own routes.

- Connections between trains are random, and long waits at interchanges are a regular feature. Each train-operating company produces its own proposed timetable plan. Fragmentation and competition law discourages it from considering the relationship with services worked by other companies. This can mean lengthy waits, adding 30 or even 60 minutes in the case of hourly services to offered journey times. You can readily find examples of this in services from Edinburgh Waverley, York, Peterborough, Carlisle, and others.

- Intervals between trains are often erratic and departure times vary. Incorporation of Open-access demands and expectations, and of the specific requirements of freight operators, has led to the abandonment of repeating timings across large parts of the network. In contrast, standard timings are commonplace in mainland Europe, particularly in Switzerland and the Netherlands.

- Printed versions have all but disappeared.

- Journey planners are poorly designed. National Rail’s Journey Planner is in many ways an excellent tool. However it presupposes knowledge about stations, it is burdened with complicated pricing, it sometimes confuses by finding clever options that no traveller would use, and where services are frequent it does not explain this convenience (for example when crossing London from a northern terminal).

How did we get to this dire state? We can thank the Railways Act 1993, which introduced competition between train operating companies. It ignored the strong ongoing challenge from other modes (cars, coaches and planes, and electronic communications). And it necessitated a Regulator, the Office of Rail and Road, whose approach is legalistic and whose decisions are incompatible with the complex task of planning workable timetables. Add to this the fragmentation of the industry, and profit-seeking Open-access companies, and you have a recipe for chaos.

The two ways of timetabling a public transport service

- An operator can plan a commercially viable timetable in competition with other firms, and fill seats by marketing travel as a commodity.

- An operator or public authority can provide journey opportunities that cater for the wide range of people’s movement requirements. Its convenience attracts users.

Privatisation encouraged the first. In most European countries the second model is offered by a state-owned railway with limited competition from private operators.

In Britain the difference is made worse by the 1993 Act. Access to the tracks for any operator is determined by the Office for Rail and Road as a legal right, independently of its workability in a timetable plan. This is just daft.

Operators are also bound by competition law that prohibits effective collaboration. It is then the task of Network Rail to arrange a timetable that satisfies these legal rights. As a result, planning safe, attractive and robust rail timetables for multi-purpose lines is incredibly challenging.

Why Open-access operators add to the problem

Open-access operators are defined as train companies who buy paths on a chosen route, and run their services on existing tracks. Open-access rights, while enabling fresh services that are understandably popular, introduce unwelcome operational and planning problems. These flaws, listed below, must be offset against any benefits that Open-access operations offer:

- Operational inefficiencies - their trains can’t be used by other companies, so an open-access service scheduled to make a return journey could be taking up valuable track and platform space

- Built-in unreliability - because smaller fleets of trains means less flexibility in the event of technical problems than larger ones

- Reduction of effective frequency - because any restriction on which trains a ticket is valid for reduces available frequency, flexibility, and choice

- Confusion for travellers regarding exclusive tickets - because buying a ticket without restrictions on whose trains you use to travel must be simpler and more customer-friendly

- Complication of the fare system - Open-access companies set their own fares for their own services, overloading an already complicated range of ticket types and prices.

- Profit before people - Open-access transfers money from public funds to private, and in some cases foreign, companies.

The Government must reject self-interested lobbying on behalf of a tiny segment of the railway’s offer. The forthcoming Railways Bill must remove the discredited concept of regulated competition. Before the election in 2024 the Labour Party published Getting Britain Moving – a vision of a transport system designed to work in the public interest. In government, reform of our railway must realise that vision.

Railway timetables: how to fix the problem

If the government is serious about Getting Britain Moving it should be working towards a comprehensive, integrated service of buses and trains that attracts travellers out of private cars. Their goal must be to relieve congestion and to protect the environment while securing good travel opportunities for those who have no car and who should not be socially and economically disadvantaged in a caring society. This is about planning the optimal use of capacity.

The specification for the rail network would be:

- a mix of frequent services appropriate to the route and the places served, and each running at least hourly

- available daily from early morning to late evening

- repetition of readily-memorable timings

- careful decisions, based on rigorous research into demand, regarding through services, and - where they are not justified - logically-designed connections at every interchange

- bus networks complementing the railway with excellent physical and well-timed connections

- presentation as a national service providing for almost all journeys at an attractive price

- high standards of layouts and signage to assist travellers throughout their journeys, especially disabled people and those unfamiliar with the system

- delivered under contract by nationally-owned operators to common standards and perhaps supplemented locally by community-interest groups; and

- that the whole system is designed to be highly reliable.

This scheme would emphasise the public interest and seek a balance between the ambitions for local services, the national importance of fast trains connecting large towns and cities, and the desirability of conveying more freight by rail. In the words of the Chief Executive of Network Rail we “need to coalesce around what the railway can do better than anyone else, and concentrate on that”. There would be no place for disruptive private companies.

This primary task by Great British Railways – and one should not underestimate the technical challenge – would offset disillusion and excite interest in the new organisation and the transformation it offers. The relief of social isolation, ending the waste of competition and the savings for the environment would justify it, as studies by Transport for Quality of Life and the Campaign for Better Transport have clearly demonstrated. And we know how successful such a policy has been in supporting the trains and buses and hence communal life in Switzerland.

Jonathan Tyler

Passenger Transport Networks

Comments

Des Appleby 6 months ago

I used trains a lot even in the days of steam to get to school, after school and a few years working local in London I was moved to Liverpool and was on the first electrified train back to London, the trains weren't perfect but better than privatisation. So if you go back to or keep the old system, then you might as well forget about changing anything and keep the CRAP we have now

Reply

https://saveplus.ae/ 3 months ago

Rail timetables might seem dull, but with public ownership, schedules can truly serve passengers—more reliability, better connections, and smarter travel. It’s about efficiency and savings for all.

Reply